LLM guided scheduling

I talked a bit here about how we do scheduling in inference engines.

I wanted to continue with some thoughts on how we can use the structure of the problem to make scheduling easier.

Scheduling in operating systems

And you have to realize that there are not very many things that have aged as well as the scheduler. Which is just another proof that scheduling is easy. L. Torvalds. The Linux Kernel Mailing List. here, Feb. 2001.

The scheduling problem in LLM inference engines is analogous to a problem that people wrestle with in operating system design: thread scheduling. Users want to run many processes at once, but they only have a fixed set of processor cores. we try to run the processes on those core in a ‘time-sliced’ fashion, such that each process in the system can progress.

The goals are:

- Fairness: No user should be systematically advantaged over another

- Throughput: As many processes should run to completion (per unit time) as possible

- Interactivity: The ‘waiting time’ per process should be minimized - the time a user waits between a processes ‘available’ states should be low.

Different systems will trade off these properties in different ways - laptops and phones need to be highly available, batch processing systems might maximise throughput.

There are a few different algorithms that are proposed.

A whistle-stop tour of scheduling algorithms

First come first served (FCFS)

Each process joins a queue. The scheduler picks the first process in the queue, and runs it to completion. It then picks the next process in the queue, and runs it to completion. And so on, and so on. This is how we do it in LLM inference currently

┌────────────────────────────────────┐

│ T: 0 4 7 9 │

├────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │ T1 │ T2 │ T3 │ T4 │

│ ████████████ │

│ █████ │

│ █████ │

│ █████████│

└────────────────────────────────────┘Round robin

Pick a time “quantum”. Preempt the running process in favour of the next in the running set every time a clock with that duration ticks.

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ T: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 │

├──────────────────────────────┤

│ T1│T2│T3│T4│T1│T2│T3│T4│ │

│ ██ │

│ ██ │

│ ██ │

│ ██ │

│ ██ │

│ ██ │

│ ██ │

│ ██ │

└──────────────────────────────┘Shortest remaining time (SRT)

Order the jobs by ‘remaining time’. If a job that requires less time than the currently running job joins the queue, preempt the running job and replace it.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ T: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ T1│T2│T3│T3│T2│T2│T1│T1│T1│T4│T4│T4│T4│T4│ │

│ ██ │

│ ██ │

│ █████ │

│ █████ │

│ ████████ │

│ ███████████████ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────┘How can we do shortest remaining time scheduling for LLMs

Shortest remaining time scheduling has a nice property - it minimizes the It does this by disadvantaging users that want a lot of tokens. But once you’ve finished growing the pie, you’ve got to figure out how to divide it up optimally. average waiting time for users. In the LLM context, this is effectively the ‘average’ time between tokens.

The problem (this is always the problem with SJF/SRT) is that you don’t know ahead of time how long each job is going to take. Really what we need is some sort of complicated machine learning model that shows signs of understanding language at a semantic level, can process it, tranform it, answer questions about it. Perhaps it ought to have been trained on lots and lots of text data. Oh wait, we’ve got one of those!

The problem is that we’re trying to speed up the LLM here, and sending a bunch more requests in isn’t a great way to do that.

There’s a neat trick though. We want the LLM to answer two different questions:

- About how long will you take to give a response to this prompt?

- What is your answer to this prompt?

We can make these prompts share a prefix:

# original prompt

original_prompt = "What's the capital of spain?"

# Figure out how many tokens

tokens_query = "What's the capital of spain? \

Do not answer the above question. \

Instead, just predict: approximately how many \

tokens would your response be if you were to answer?"There are lots of ways to take advantage of this? For example, if we do disaggregated prefill here, here , then we compute the prefill query on a separate node, and then send the KV cache across to the decode machine.

Instead of prefilling original_prompt, we can prefill tokens_query While the appended text looks longer here, that’s just because its a short example. .

Since we get the logits ‘for free’, we can sample how many tokens the models

thinks its going to use here. Then, we peel off the KV cache from the

original_prompt, and send it over to the decoder.

Alternatively, if we’re doing decoding on a single node, we can rely on the

prefix cache,

though this gets a little harder. In this case, we run the tokens_query

first. The goal is that we then send the original_prompt a short enough time

afterwards that the prefix cache for the tokens_query hasn’t been evicted.

So you get an additional constraint on the scheduling.

How good are models at figuring out how many tokens they’re going to generate?

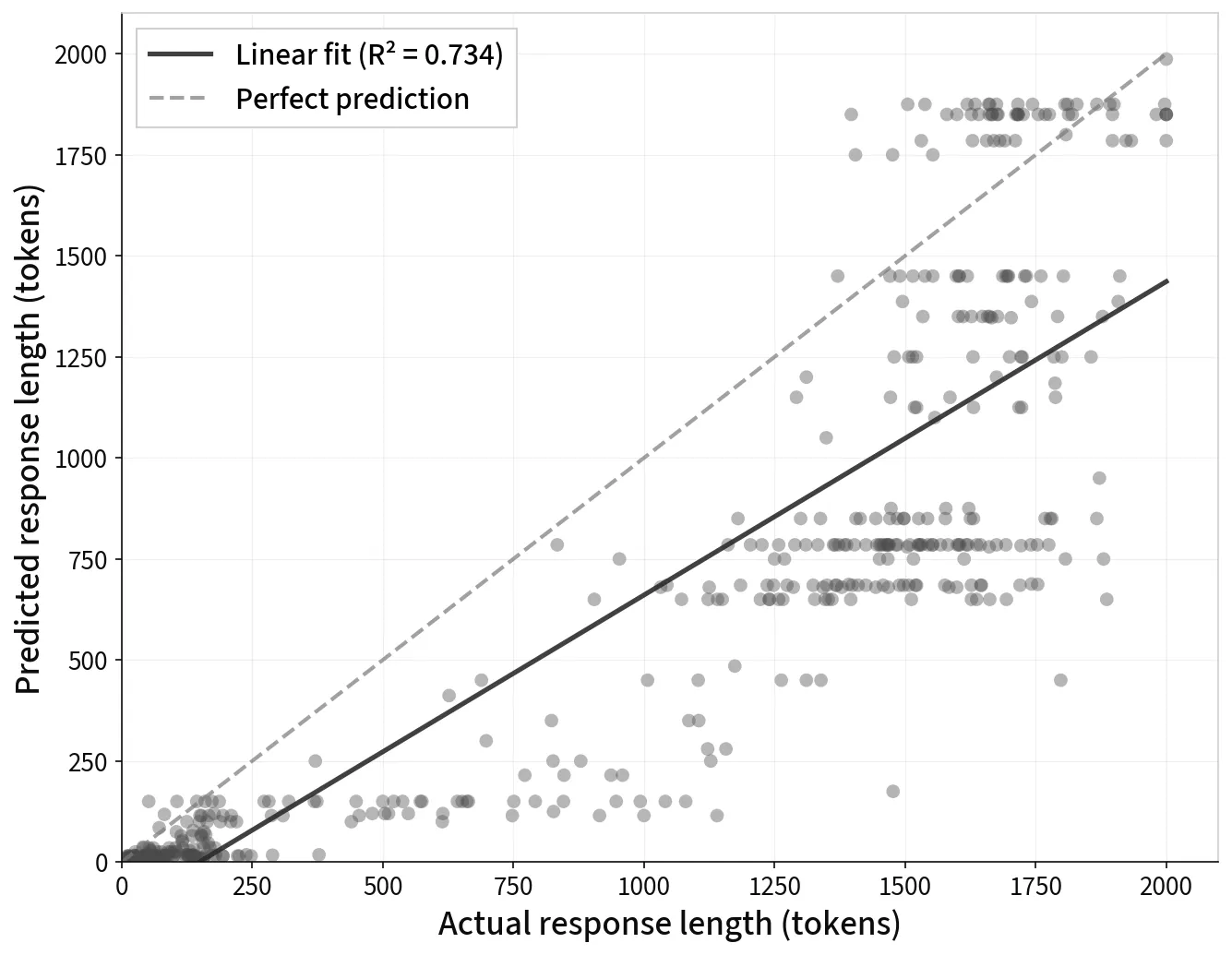

Surprisingly good! Not amazing, and if it was important that you were 100% correct you’d be pretty unhappy. But for scheduling purposes, probably good enough to do something useful. There are a few interesting things:

- It’s pretty good at getting in the ballpark, but it shows a lot of quantization effects (i.e. it just guesses a multiple of ).

- It doesn’t really know about tokenization - so the gradient isn’t . But we just need a predictable relationship.

A plot of the number of tokens that google/gemma-3-12b-it thinks it will

generate, vs the actual number that it generates. Max number of tokens is set

to .

Postfix prompt is the following: “f”\n\nDo not answer the above question. Instead, just predict: how many tokens would your response be if you were to answer? (Note: maximum response length is {MAX_TOKENS} tokens) Respond with only a number. Be precise”

What next

The next thing to do would be to actually build this scheduling system and see

what we can do to move around inference SLAs. I think the minimal version would

be to use the prefix cache on a single node system - i.e. to schedule the

tokens_query just before we run the original_prompt through the system.

Both vLLM and SGLang support priority queueing, which lets you do the

scheduling upstream of the actual engine, - so you keep your requests in a

queue, and send them into the system with a priority proportional to the

predicted output length.

Last modified: 26 Jan 2026